| If Ever You Go to Dublin Town (оригінал) | If Ever You Go to Dublin Town (переклад) |

|---|---|

| If you ever go to Dublin town | Якщо ви коли-небудь поїдете в Дублін |

| In a hundred years or so | Через сотню років або близько того |

| Inquire for me in Baggot street | Запитуйте мене на Баггот-стріт |

| And what I was like to know | І те, що я хотів знати |

| O he was the queer one | О, він був дивним |

| Fol dol the di do | Fol dol the di do |

| He was a queer one | Він був дивним |

| And I tell you | І я кажу вам |

| My great-grandmother knew him well, | Моя прабабуся добре знала його, |

| He asked her to come and call | Він попросив її прийти і подзвонити |

| On him in his flat and she giggled at the thought | На його в його квартирі, і вона хихикала при думці |

| Of a young girl’s lovely fall. | Чудова осінь молодої дівчини. |

| O he was dangerous, | О він був небезпечний, |

| Fol dol the di do, | Fol dol the di do, |

| He was dangerous, | Він був небезпечним, |

| And I tell you | І я кажу вам |

| On Pembroke Road look out for me ghost, | На Пембрук-роуд шукай мене привид, |

| Dishevelled with shoes untied, | Розпатланий з розв'язаними черевиками, |

| Playing through the railings with little children | Граються через перила з маленькими дітьми |

| Whose children have long since died. | Чиї діти давно померли. |

| O he was a nice man, | О він був гарна людина, |

| Fol do the di do, | Fol do the di do, |

| He was a nice man | Він був гарною людиною |

| And I tell you | І я кажу вам |

| Go into a pub and listen well | Зайдіть у паб і добре послухайте |

| If my voice still echoes there, | Якщо мій голос все ще лунає там, |

| Ask the men what their grandsires thought | Запитайте чоловіків, що думали їхні прадіди |

| And tell them to answer fair, | І скажіть їм відповідати чесно, |

| O he was eccentric, | О він був ексцентричним, |

| Fol do the di do, | Fol do the di do, |

| He was eccentric | Він був ексцентричним |

| And I tell you | І я кажу вам |

| He had the knack of making men feel | Він вмів викликати у чоловіків почуття |

| As small as they really were | Настільки малі, якими вони були насправді |

| Which meant as great as God had made them | Це означало настільки великими, якими їх створив Бог |

| But as males they disliked his air. | Але як чоловіки вони не любили його повітря. |

| O he was a proud one, | О він був гордий, |

| Fol do the di do, | Fol do the di do, |

| He was a proud one | Він був гордий |

| And I tell you | І я кажу вам |

| If ever you go to Dublin town | Якщо ви колись поїдете в Дублін |

| In a hundred years or so | Через сотню років або близько того |

| Sniff for my personality, | Понюхайте мою особистість, |

| Is it Vanity’s vapour now? | Чи це випарення Ванті? |

| O he was a vain one, | О він був марний, |

| Fol dol the di do, | Fol dol the di do, |

| He was a vain one | Він був марним |

| And I tell you | І я кажу вам |

| I saw his name with a hundred more | Я бачив його ім’я разом із сотней інших |

| In a book in the library, | У книзі в бібліотеці, |

| It said he had never fully achieved | Там сказано, що він ніколи не досягав повністю |

| His potentiality. | Його потенціал. |

| O he was slothful, | О він був лінивий, |

| Fol do the di do, | Fol do the di do, |

| He was slothful | Він був лінивим |

| And I tell you | І я кажу вам |

| He knew that posterity had no use | Він знав, що нащадкам немає користі |

| For anything but the soul, | За все, крім душі, |

| The lines that speak the passionate heart, | Рядки, що промовляють пристрасне серце, |

| The spirit that lives alone. | Дух, що живе один. |

| O he was a lone one, | О він був самотній, |

| Fol do the di do | Fol do the di do |

| O he was a lone one, | О він був самотній, |

| And I tell you | І я кажу вам |

| O he was a lone one, | О він був самотній, |

| Fol do the di do | Fol do the di do |

| Yet he lived happily | Але він жив щасливо |

| And I tell you. | І я кажу вам. |

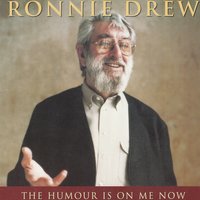

Переклад тексту пісні If Ever You Go to Dublin Town - Ronnie Drew

Інформація про пісню На цій сторінці ви можете ознайомитися з текстом пісні If Ever You Go to Dublin Town , виконавця -Ronnie Drew

Пісня з альбому: The Humour Is On Me Now

У жанрі:Кельтская музыка

Дата випуску:02.03.1999

Мова пісні:Англійська

Лейбл звукозапису:Dolphin

Виберіть якою мовою перекладати:

Напишіть, що ви думаєте про текст пісні!

Інші пісні виконавця:

| Назва | Рік |

|---|---|

| 2014 | |

| 2014 | |

| 2014 | |

| 1999 | |

| 2009 | |

| 2009 | |

| 2009 | |

| 1988 | |

| 2014 | |

| 2016 | |

| 2014 | |

| 2014 | |

| 2014 |