| Berenice (оригінал) | Berenice (переклад) |

|---|---|

| MISERY is manifold. | МІЗЕРІ різноманітна. |

| The wretchedness of earth is multiform. | Злиденність землі багатогранна. |

| Overreaching the | Перевищення |

| wide | широкий |

| horizon as the rainbow, its hues are as various as the hues of that arch, | горизонт, як веселка, її відтінки такі ж різноманітні, як відтінки цієї арки, |

| —as distinct too, | — теж як відмінний, |

| yet as intimately blended. | але як тісно змішані. |

| Overreaching the wide horizon as the rainbow! | Охоплюючи широкий горизонт, як веселка! |

| How is it | Як це |

| that from beauty I have derived a type of unloveliness? | що з краси я отримав тип нелюбовності? |

| —from the covenant of | — із заповіту о |

| peace a | мир а |

| simile of sorrow? | порівняння смутку? |

| But as, in ethics, evil is a consequence of good, so, in fact, | Але оскільки в етиці зло є наслідком добра, отже, насправді, |

| out of joy is | від радості є |

| sorrow born. | скорбота народжена. |

| Either the memory of past bliss is the anguish of to-day, | Або спогад про минуле блаженство — це мука сьогодні, |

| or the agonies | або агонії |

| which are have their origin in the ecstasies which might have been. | які мають своє походження в екстазі, який міг бути. |

| My baptismal name is Egaeus; | Моє ім’я під час хрещення Егей; |

| that of my family I will not mention. | про свою сім’ю я не буду згадувати. |

| Yet there are no | Але їх немає |

| towers in the land more time-honored than my gloomy, gray, hereditary halls. | вежі в країні, більш шанованій часом, ніж мої похмурі, сірі, спадкові зали. |

| Our line | Наша лінія |

| has been called a race of visionaries; | називали расою візіонерів; |

| and in many striking particulars —in the | і в багатьох вражаючих подробицях — у |

| character | характер |

| of the family mansion —in the frescos of the chief saloon —in the tapestries of | родинного особняка — у фресках головного салону — у гобеленах |

| the | в |

| dormitories —in the chiselling of some buttresses in the armory —but more | гуртожитки — у різанні деяких контрфорсів у збройовій — але більше |

| especially | особливо |

| in the gallery of antique paintings —in the fashion of the library chamber —and, | у галереї антикварних картин — за модою зали бібліотеки — і, |

| lastly, | нарешті, |

| in the very peculiar nature of the library’s contents, there is more than | у дуже своєрідному характері вмісту бібліотеки є більш ніж |

| sufficient | достатній |

| evidence to warrant the belief. | докази, які підтверджують віру. |

| The recollections of my earliest years are connected with that chamber, | З тією кімнатою пов’язані спогади моїх ранніх років, |

| and with its | і з його |

| volumes —of which latter I will say no more. | томи — про останній я більше не скажу. |

| Here died my mother. | Тут померла моя мати. |

| Herein was I born. | Тут я народився. |

| But it is mere idleness to say that I had not lived before | Але говорити, що раніше я не жив, це просто лінь |

| —that the | -що |

| soul has no previous existence. | душа не має попереднього існування. |

| You deny it? | Ви це заперечуєте? |

| —let us not argue the matter. | — давайте не сперечатися. |

| Convinced myself, I seek not to convince. | Переконаний сам, я прагну не переконувати. |

| There is, however, a remembrance of | Однак є спогад про |

| aerial | повітряний |

| forms —of spiritual and meaning eyes —of sounds, musical yet sad —a remembrance | форми — духовних і смислових очей — звуків, музичних, але сумних — спогад |

| which will not be excluded; | які не будуть виключені; |

| a memory like a shadow, vague, variable, indefinite, | пам'ять, як тінь, розпливчаста, змінна, невизначена, |

| unsteady; | непостійний; |

| and like a shadow, too, in the impossibility of my getting rid of it | і, як тінь, також у неможливості позбутися її |

| while the | в той час як |

| sunlight of my reason shall exist. | сонячне світло мого розуму буде існувати. |

| In that chamber was I born. | У тій кімнаті я народився. |

| Thus awaking from the long night of what seemed, | Таким чином, прокинувшись від довгої ночі, що здавалося, |

| but was | але був |

| not, nonentity, at once into the very regions of fairy-land —into a palace of | не, нікчема, відразу в самі краї казкової країни — в палац |

| imagination | уява |

| —into the wild dominions of monastic thought and erudition —it is not singular | — у дикі панування чернечої думки та ерудиції — це не є єдиним |

| that I | що я |

| gazed around me with a startled and ardent eye —that I loitered away my boyhood | дивився довкола мене враженим і палким оком, що я пропустив своє дитинство |

| in | в |

| books, and dissipated my youth in reverie; | книжки, і розвіяв свою молодість у задумах; |

| but it is singular that as years | але це особливе, що як роки |

| rolled away, | відкотився, |

| and the noon of manhood found me still in the mansion of my fathers —it is | і полудень мужності застав мене все ще в особняку моїх батьків — це |

| wonderful | чудовий |

| what stagnation there fell upon the springs of my life —wonderful how total an | який застій впав на пружини мого життя — дивовижно, наскільки повний |

| inversion took place in the character of my commonest thought. | інверсія відбулася в характері моєї найпоширенішої думки. |

| The realities of | Реалії с |

| the | в |

| world affected me as visions, and as visions only, while the wild ideas of the | світ вплинув на мене як видіння, і лише як видіння, тоді як дикі ідеї |

| land of | землі |

| dreams became, in turn, —not the material of my every-day existence-but in very | мрії стали, у свою чергу, — не матеріалом мого повсякденного існування, але дуже |

| deed | вчинок |

| that existence utterly and solely in itself. | це існування цілком і виключно в собі. |

| - | - |

| Berenice and I were cousins, and we grew up together in my paternal halls. | Ми з Береніс були двоюрідними братами, і ми виросли разом у моїх батьківських сім’ях. |

| Yet differently we grew —I ill of health, and buried in gloom —she agile, | Але по-різному ми росли —Я хворий, і похований у мороці —вона спритна, |

| graceful, and | витончений, і |

| overflowing with energy; | переповнений енергією; |

| hers the ramble on the hill-side —mine the studies of | її прогулянка на схилі пагорба — моє дослідження |

| the | в |

| cloister —I living within my own heart, and addicted body and soul to the most | монастир — я живу у своєму власному серці, і найбільше залежний тілом і душею |

| intense | інтенсивний |

| and painful meditation —she roaming carelessly through life with no thought of | і болісна медитація — вона безтурботно блукає по життю, не думаючи про це |

| the | в |

| shadows in her path, or the silent flight of the ravenwinged hours. | тіні на її шляху чи безшумний політ воронкрилих годин. |

| Berenice! | Береніс! |

| —I call | — дзвоню |

| upon her name —Berenice! | на її ім'я — Береніс! |

| —and from the gray ruins of memory a thousand | — і з сивих руїн пам’яті тисяча |

| tumultuous recollections are startled at the sound! | бурхливі спогади вражають звуку! |

| Ah! | Ах! |

| vividly is her image | яскравим є її образ |

| before me | перед мною |

| now, as in the early days of her lightheartedness and joy! | тепер, як і в перші дні її безтурботності та радості! |

| Oh! | О! |

| gorgeous yet | ще чудовий |

| fantastic | фантастичний |

| beauty! | краса! |

| Oh! | О! |

| sylph amid the shrubberies of Arnheim! | сильфія серед кущів Арнхайма! |

| —Oh! | — О! |

| Naiad among its | Наяда серед своїх |

| fountains! | фонтани! |

| —and then —then all is mystery and terror, and a tale which should not be told. | — а потім — тоді все — таємниця й жах, і казка, яку не варто розповідати. |

| Disease —a fatal disease —fell like the simoom upon her frame, and, even while I | Хвороба — смертельна хвороба — впала, як симум, на її тіло, і навіть тоді, коли я |

| gazed upon her, the spirit of change swept, over her, pervading her mind, | дивився на неї, дух змін охопив її, пронизуючи її розум, |

| her habits, | її звички, |

| and her character, and, in a manner the most subtle and terrible, | і її характер, і, в найвитонченішій і жахливій манері, |

| disturbing even the | заважаючи навіть |

| identity of her person! | особистість її особи! |

| Alas! | на жаль! |

| the destroyer came and went, and the victim | руйнівник прийшов і пішов, і жертва |

| —where was | -де був |

| she, I knew her not —or knew her no longer as Berenice. | вона, я її не знав — або більше не знав як Береніс. |

| Among the numerous train of maladies superinduced by that fatal and primary one | Серед численних захворювань, викликаних цією смертельною та первинною |

| which effected a revolution of so horrible a kind in the moral and physical | яка спричинила революцію такого жахливого виду в моральному та фізичному плані |

| being of my | бути моїм |

| cousin, may be mentioned as the most distressing and obstinate in its nature, | двоюрідний брат, можна згадати як найболючішу та вперту за своєю натурою, |

| a species | вид |

| of epilepsy not unfrequently terminating in trance itself —trance very nearly | епілепсія, яка нерідко закінчується трансом — дуже майже трансом |

| resembling positive dissolution, and from which her manner of recovery was in | нагадує позитивне розчинення, і від чого полягала її манера відновлення |

| most | більшість |

| instances, startlingly abrupt. | випадки, напрочуд різкі. |

| In the mean time my own disease —for I have been | Тим часом моя власна хвороба — бо я був |

| told | розповів |

| that I should call it by no other appelation —my own disease, then, | що я повинен називати це не інакше — моєю власною хворобою, |

| grew rapidly upon | швидко зростав |

| me, and assumed finally a monomaniac character of a novel and extraordinary | мене, і нарешті прийняв мономанський характер роману та надзвичайного |

| form — | форма — |

| hourly and momently gaining vigor —and at length obtaining over me the most | щогодини й миттєво набираючи сили — і з часом переймаючи мене найбільше |

| incomprehensible ascendancy. | незрозуміле панування. |

| This monomania, if I must so term it, consisted in a morbid irritability of | Ця мономанія, якщо я повинен так висловитися, полягала в хворобливій дратівливості |

| those | ті |

| properties of the mind in metaphysical science termed the attentive. | властивості розуму в метафізичній науці називають уважним. |

| It is more than | Це більше ніж |

| probable that I am not understood; | ймовірно, що мене не зрозуміли; |

| but I fear, indeed, that it is in no manner | але я справді боюся, що це жодним чином |

| possible to | можливо |

| convey to the mind of the merely general reader, an adequate idea of that | донести до розуму простого читача адекватне уявлення про це |

| nervous | нервовий |

| intensity of interest with which, in my case, the powers of meditation (not to | інтенсивність інтересу, з якою, у моєму випадку, здатність до медитації (не для |

| speak | говорити |

| technically) busied and buried themselves, in the contemplation of even the most | технічно) зайняті та поховані, у спогляданні навіть найбільше |

| ordinary objects of the universe. | звичайні об’єкти Всесвіту. |

| To muse for long unwearied hours with my attention riveted to some frivolous | Музувати протягом довгих невтомних годин, прикуваючи увагу до деяких легковажних |

| device | пристрій |

| on the margin, or in the topography of a book; | на полях або в топографії книги; |

| to become absorbed for the | щоб захопитися |

| better part of | краща частина |

| a summer’s day, in a quaint shadow falling aslant upon the tapestry, | літній день, у химерній тіні, що косо падає на гобелен, |

| or upon the door; | або на дверях; |

| to lose myself for an entire night in watching the steady flame of a lamp, | втратити себе на цілу ніч, спостерігаючи за рівним полум’ям лампи, |

| or the embers | або вугілля |

| of a fire; | пожежі; |

| to dream away whole days over the perfume of a flower; | мріяти цілі дні над ароматом квітки; |

| to repeat | повторити |

| monotonously some common word, until the sound, by dint of frequent repetition, | монотонно якесь загальне слово, поки звук, завдяки частому повторенню, |

| ceased to convey any idea whatever to the mind; | перестав передати будь-яку ідею розуму; |

| to lose all sense of motion or | втратити відчуття руху або |

| physical | фізичний |

| existence, by means of absolute bodily quiescence long and obstinately | існування, за допомогою абсолютного тілесного спокою, тривалого та впертого |

| persevered in; | persevered in; |

| —such were a few of the most common and least pernicious vagaries induced by a | — такими були кілька найпоширеніших і найменш згубних примх, спричинених a |

| condition of the mental faculties, not, indeed, altogether unparalleled, | стан розумових здібностей, справді, не зовсім незрівнянний, |

| but certainly | але звичайно |

| bidding defiance to anything like analysis or explanation. | заперечувати будь-що, як аналіз чи пояснення. |

| Yet let me not be misapprehended. | Але нехай мене не зрозуміють неправильно. |

| —The undue, earnest, and morbid attention thus | — Надмірна, серйозна й хвороблива увага |

| excited by objects in their own nature frivolous, must not be confounded in | схвильований об’єктами за своєю власною природою легковажними, не слід плутати з |

| character | характер |

| with that ruminating propensity common to all mankind, and more especially | з тією схильністю до роздумів, яка є спільною для всього людства, і особливо |

| indulged | потурали |

| in by persons of ardent imagination. | в людьми з палкою уявою. |

| It was not even, as might be at first | Це не було навіть, як може бути спочатку |

| supposed, an | передбачуваний, ан |

| extreme condition or exaggeration of such propensity, but primarily and | крайній стан або перебільшення такої схильності, але в першу чергу і |

| essentially | по суті |

| distinct and different. | відмінні та різні. |

| In the one instance, the dreamer, or enthusiast, | В одному випадку, мрійник або ентузіаст, |

| being interested | бути зацікавленим |

| by an object usually not frivolous, imperceptibly loses sight of this object in | об’єктом зазвичай несерйозно, непомітно втрачає цей об’єкт із поля зору в |

| wilderness of deductions and suggestions issuing therefrom, until, | пустеля відрахувань і пропозицій, що виходять звідти, доки, |

| at the conclusion of | на завершення |

| a day dream often replete with luxury, he finds the incitamentum or first cause | денна мрія, часто наповнена розкішшю, він знаходить підказку або першопричину |

| of his | його |

| musings entirely vanished and forgotten. | міркування зовсім зникли й забулися. |

| In my case the primary object was | У моєму випадку основним об’єктом було |

| invariably | незмінно |

| frivolous, although assuming, through the medium of my distempered vision, a | несерйозно, хоча й припускаю, через моє роздратоване бачення, a |

| refracted and unreal importance. | заломлене і нереальне значення. |

| Few deductions, if any, were made; | Було зроблено небагато відрахувань, якщо такі були; |

| and those few | і тих небагатьох |

| pertinaciously returning in upon the original object as a centre. | наполегливо повертаючись до оригінального об’єкта як до центру. |

| The meditations were | Медитації були |

| never pleasurable; | ніколи не приносить задоволення; |

| and, at the termination of the reverie, the first cause, | і, після припинення мрії, перша причина, |

| so far from | так далеко від |

| being out of sight, had attained that supernaturally exaggerated interest which | перебуваючи поза полем зору, досяг того надприродно перебільшеного інтересу, який |

| was the | був |

| prevailing feature of the disease. | переважна ознака захворювання. |

| In a word, the powers of mind more | Одним словом, сили розуму більше |

| particularly | зокрема |

| exercised were, with me, as I have said before, the attentive, and are, | були зі мною, як я вже казав раніше, уважними, і, |

| with the daydreamer, | з мрійником, |

| the speculative. | спекулятивний. |

| My books, at this epoch, if they did not actually serve to irritate the | Мої книги, у цю епоху, якби вони насправді не служили для дратування |

| disorder, partook, it | розлад, участь, це |

| will be perceived, largely, in their imaginative and inconsequential nature, | будуть сприйняті, в основному, через їхню уявну та несуттєву природу, |

| of the | з |

| characteristic qualities of the disorder itself. | характерні якості самого розладу. |

| I well remember, among others, | Я добре пам’ятаю, серед іншого, |

| the treatise | трактат |

| of the noble Italian Coelius Secundus Curio «de Amplitudine Beati Regni dei»; | знатного італійця Целія Секунда Куріона «de Amplitudine Beati Regni dei»; |

| St. | вул. |

| Austin’s great work, the «City of God»; | Велика робота Остіна «Місто Бога»; |

| and Tertullian «de Carne Christi,» | і Тертулліан «de Carne Christi» |

| in which the | в якому |

| paradoxical sentence «Mortuus est Dei filius; | парадоксальне речення «Mortuus est Dei filius; |

| credible est quia ineptum est: | надійний est quia ineptum est: |

| et sepultus | et sepultus |

| resurrexit; | resurrexit; |

| certum est quia impossibile est» occupied my undivided time, | certum est quia impossibile est» зайняв мій нерозділений час, |

| for many | для багатьох |

| weeks of laborious and fruitless investigation. | тижні трудомісткого та безрезультатного розслідування. |

| Thus it will appear that, shaken from its balance only by trivial things, | Таким чином буде здаватися, що, порушивши рівновагу лише тривіальними речами, |

| my reason bore | мій розум спровокував |

| resemblance to that ocean-crag spoken of by Ptolemy Hephestion, which steadily | схожість на ту океанську скелю, про яку говорив Птолемей Гефестіон, яка постійно |

| resisting the attacks of human violence, and the fiercer fury of the waters and | протистояти нападам людського насильства та лютішій люті вод і |

| the | в |

| winds, trembled only to the touch of the flower called Asphodel. | вітри, тремтіли лише від дотику квітки під назвою Асфодель. |

| And although, to a careless thinker, it might appear a matter beyond doubt, | І хоча для недбалого мислителя це може здатися безсумнівним, |

| that the | що |

| alteration produced by her unhappy malady, in the moral condition of Berenice, | зміни, спричинені її нещасною хворобою, у моральному стані Беренік, |

| would | б |

| afford me many objects for the exercise of that intense and abnormal meditation | дайте мені багато предметів для вправ цієї інтенсивної та ненормальної медитації |

| whose | чий |

| nature I have been at some trouble in explaining, yet such was not in any | природу я мав деякі проблеми з поясненням, але такого не було ні в одному |

| degree the | ступінь |

| case. | справа. |

| In the lucid intervals of my infirmity, her calamity, indeed, | У ясних проміжках моєї немочі, її лиха, справді, |

| gave me pain, and, | завдав мені болю, і, |

| taking deeply to heart that total wreck of her fair and gentle life, | беручи глибоко до серця цей повний крах її справедливого та ніжного життя, |

| I did not fall to ponder | Я не впав роздумувати |

| frequently and bitterly upon the wonderworking means by which so strange a | часто і з гіркотою на чудотворні засоби, за допомогою яких так дивно a |

| revolution had been so suddenly brought to pass. | революція була так раптово здійснена. |

| But these reflections partook | Але ці роздуми взяли участь |

| not of | не з |

| the idiosyncrasy of my disease, and were such as would have occurred, | ідіосинкразія моєї хвороби, і якби це сталося, |

| under similar | під подібні |

| circumstances, to the ordinary mass of mankind. | обставини, для звичайних мас людства. |

| True to its own character, | Вірний власному характеру, |

| my disorder | мій розлад |

| revelled in the less important but more startling changes wrought in the | насолоджувався менш важливими, але більш разючими змінами, які відбулися в |

| physical frame | фізичний каркас |

| of Berenice —in the singular and most appalling distortion of her personal | Беренік — у винятковому та найжахливішому спотворенні її особистого |

| identity. | ідентичність. |

| During the brightest days of her unparalleled beauty, most surely I had never | У найяскравіші дні її незрівнянної краси я, напевно, ніколи не був |

| loved | любив |

| her. | її. |

| In the strange anomaly of my existence, feelings with me, had never been | У дивній аномалії мого існування, почуттів зі мною ніколи не було |

| of the | з |

| heart, and my passions always were of the mind. | серце, і мої пристрасті завжди були розумом. |

| Through the gray of the early | Крізь сірість раннього |

| morning —among the trellissed shadows of the forest at noonday —and in the | ранок — серед ґратчастих тіней лісу опівдні — і в |

| silence | тиша |

| of my library at night, she had flitted by my eyes, and I had seen her —not as | моєї бібліотеки вночі, вона промайнула повз мої очі, і я бачив її — не як |

| the living | живий |

| and breathing Berenice, but as the Berenice of a dream —not as a being of the | і дихає Береніка, але як Береніка мрії — а не як істота |

| earth, | земля, |

| earthy, but as the abstraction of such a being-not as a thing to admire, | земний, але як абстракція такого буття, а не як річ, якою можна захоплюватися, |

| but to analyze — | але аналізувати — |

| not as an object of love, but as the theme of the most abstruse although | не як об’єкт кохання, а як тема самого незрозумілого |

| desultory | необов'язковий |

| speculation. | спекуляції. |

| And now —now I shuddered in her presence, and grew pale at her | І тепер — тепер я здригнувся в її присутності, і зблід від неї |

| approach; | підхід; |

| yet bitterly lamenting her fallen and desolate condition, | все ж гірко оплакуючи свій занепалий і спустошений стан, |

| I called to mind that | Я згадав це |

| she had loved me long, and, in an evil moment, I spoke to her of marriage. | вона кохала мене давно, і в лиху хвилину я заговорив з нею про одруження. |

| And at length the period of our nuptials was approaching, when, upon an | І врешті-решт наближався період нашого весілля, коли на |

| afternoon in | після обіду в |

| the winter of the year, —one of those unseasonably warm, calm, and misty days | зима року, — один із тих не по сезону теплих, спокійних і туманних днів |

| which | який |

| are the nurse of the beautiful Halcyon1, —I sat, (and sat, as I thought, alone, | годувальниця красуні Халкіон1, —Я сиділа, (і сиділа, як я думав, одна, |

| ) in the | ) в |

| inner apartment of the library. | внутрішня квартира бібліотеки. |

| But uplifting my eyes I saw that Berenice stood | Але піднявши очі, я побачив, що Береніс стоїть |

| before | раніше |

| me. | мене. |

| - | - |

| Was it my own excited imagination —or the misty influence of the atmosphere —or | Чи це була моя власна збуджена уява — чи туманний вплив атмосфери — чи |

| the | в |

| uncertain twilight of the chamber —or the gray draperies which fell around her | непевні сутінки кімнати — або сірі драпірування, що спадали навколо неї |

| figure | фігура |

| —that caused in it so vacillating and indistinct an outline? | — що викликало в ньому такий хиткий і нечіткий контур? |

| I could not tell. | Я не міг сказати. |

| She spoke no | Вона говорила ні |

| word, I —not for worlds could I have uttered a syllable. | слово, я — ні за що світи я міг вимовити склад. |

| An icy chill ran | Пробіг крижаний холодок |

| through my | через мій |

| frame; | рамка; |

| a sense of insufferable anxiety oppressed me; | почуття нестерпної тривоги гнітило мене; |

| a consuming curiosity | всепоглинаюча цікавість |

| pervaded | пронизаний |

| my soul; | моя душа; |

| and sinking back upon the chair, I remained for some time breathless | і, опустившись на спинку крісла, я деякий час залишався задиханим |

| and | і |

| motionless, with my eyes riveted upon her person. | нерухомо, з моїми очами, прикутими до неї. |

| Alas! | на жаль! |

| its emaciation was | його виснаження було |

| excessive, | надмірний, |

| and not one vestige of the former being, lurked in any single line of the | і жодного залишку колишнього буття, не причаїлося в жодній окремій лінії |

| contour. | контур. |

| My | мій |

| burning glances at length fell upon the face. | палаючі погляди в довжину впали на обличчя. |

| The forehead was high, and very pale, and singularly placid; | Лоб був високий, дуже блідий і незвичайно спокійний; |

| and the once jetty | і колись причал |

| hair fell | волосся випало |

| partially over it, and overshadowed the hollow temples with innumerable | частково над ним, і затьмарював порожнисті храми з незліченною кількістю |

| ringlets now | зараз локони |

| of a vivid yellow, and Jarring discordantly, in their fantastic character, | яскраво-жовтого кольору, і Джарринг суперечливо, у їхньому фантастичному характері, |

| with the | з |

| reigning melancholy of the countenance. | панує меланхолія на обличчі. |

| The eyes were lifeless, and lustreless, | Очі були неживі, без блиску, |

| and | і |

| seemingly pupil-less, and I shrank involuntarily from their glassy stare to the | здавалося, без зіниць, і я мимоволі зіщулився від їх скляного погляду на |

| contemplation of the thin and shrunken lips. | споглядання тонких і зморщених губ. |

| They parted; | Вони розійшлися; |

| and in a smile of | і в посмішці |

| peculiar | своєрідний |

| meaning, the teeth of the changed Berenice disclosed themselves slowly to my | тобто зуби зміненої Береніс повільно відкривалися мені |

| view. | переглянути. |

| Would to God that I had never beheld them, or that, having done so, I had died! | Якби я їх ніколи не бачив, або щоб, зробивши це, я помер! |

| 1 For as Jove, during the winter season, gives twice seven days of warmth, | 1 Бо як Юпітер під час зимової пори дає двічі по сім днів тепла, |

| men have | чоловіки мають |

| called this clement and temperate time the nurse of the beautiful Halcyon | назвав цей світлий і помірний час годувальницею прекрасного Халкіона |

| —Simonides. | — Симонід. |

| The shutting of a door disturbed me, and, looking up, I found that my cousin had | Зачинені двері занепокоїли мене, і, піднявши погляд, я виявив, що мій двоюрідний брат мав |

| departed from the chamber. | вийшов із палати. |

| But from the disordered chamber of my brain, had not, | Але від невпорядкованої камери мого мозку не було, |

| alas! | на жаль! |

| departed, and would not be driven away, the white and ghastly spectrum of | відійшов і не міг бути вигнаний, білий і жахливий спектр |

| the | в |

| teeth. | зуби. |

| Not a speck on their surface —not a shade on their enamel —not an | Жодної плями на їхній поверхні — жодного відтінку на емалі — жодного |

| indenture in | інденція в |

| their edges —but what that period of her smile had sufficed to brand in upon my | їхні краї — але те, що цього періоду її усмішки було достатньо, щоб таврувати на мені |

| memory. | пам'ять. |

| I saw them now even more unequivocally than I beheld them then. | Зараз я бачив їх ще більш однозначно, ніж бачив тоді. |

| The teeth! | Зуби! |

| —the teeth! | — зуби! |

| —they were here, and there, and everywhere, and visibly and palpably | — вони були і тут, і там, і всюди, і зримо, і відчутно |

| before me; | перед мною; |

| long, narrow, and excessively white, with the pale lips writhing | довгий, вузький і надто білий, з блідими губами, що зморщуються |

| about them, | про них, |

| as in the very moment of their first terrible development. | як у самий момент їхнього першого жахливого розвитку. |

| Then came the full | Потім настав повний |

| fury of my | лють моя |

| monomania, and I struggled in vain against its strange and irresistible | мономанії, і я марно боровся з її дивним і непереборним |

| influence. | вплив. |

| In the | В |

| multiplied objects of the external world I had no thoughts but for the teeth. | помножені об’єкти зовнішнього світу У мене не було жодних думок, крім зубів. |

| For these I | Для цих я |

| longed with a phrenzied desire. | прагнув шаленого бажання. |

| All other matters and all different interests | Всі інші справи і всі різні інтереси |

| became | став |

| absorbed in their single contemplation. | поглинені своїм єдиним спогляданням. |

| They —they alone were present to the | Вони — лише вони були присутні на |

| mental | психічний |

| eye, and they, in their sole individuality, became the essence of my mental | око, і вони, у своїй єдиній індивідуальності, стали суттю мого розуму |

| life. | життя. |

| I held | Я тримав |

| them in every light. | їх у будь-якому світлі. |

| I turned them in every attitude. | Я обернув їх у кожному відношенні. |

| I surveyed their | Я оглядав їх |

| characteristics. | характеристики. |

| I | я |

| dwelt upon their peculiarities. | зупинився на їхніх особливостях. |

| I pondered upon their conformation. | Я роздумував над їхньою структурою. |

| I mused upon the | Я роздумував над |

| alteration in their nature. | зміна їхньої природи. |

| I shuddered as I assigned to them in imagination a | Я здригнувся, коли призначив їм в уяві а |

| sensitive | чутливий |

| and sentient power, and even when unassisted by the lips, a capability of moral | і розумова сила, і навіть без допомоги вуст, здатність морального |

| expression. | вираз. |

| Of Mad’selle Salle it has been well said, «que tous ses pas etaient | Про Mad’selle Salle добре сказано: «que tous ses pas etaient |

| des | des |

| sentiments,» and of Berenice I more seriously believed que toutes ses dents | настрої», а про Береніс я серйозніше вірив у que toutes ses dents |

| etaient des | etaient des |

| idees. | ідеї. |

| Des idees! | Des idees! |

| —ah here was the idiotic thought that destroyed me! | — О, ось яка ідіотська думка знищила мене! |

| Des idees! | Des idees! |

| —ah | — ах |

| therefore it was that I coveted them so madly! | тому я так бажав їх! |

| I felt that their possession | Я відчував, що вони володіють |

| could alone | міг сам |

| ever restore me to peace, in giving me back to reason. | колись віднови мене до миру, повернувши мене до розуму. |

| And the evening closed in upon me thus-and then the darkness came, and tarried, | І вечір накрив до мене так, а потім настала темрява, і затрималася, |

| and | і |

| went —and the day again dawned —and the mists of a second night were now | пішов — і день знову світав — і туман другої ночі був зараз |

| gathering around —and still I sat motionless in that solitary room; | збираючись довкола — і я все одно сидів нерухомо в тій самотній кімнаті; |

| and still I sat buried | і все одно я сидів похований |

| in meditation, and still the phantasma of the teeth maintained its terrible | у медитації, і все ще фантазма зубів зберігала свій жах |

| ascendancy | панування |

| as, with the most vivid hideous distinctness, it floated about amid the | як, з найяскравішою огидною виразністю, він плавав посеред |

| changing lights | зміна світла |

| and shadows of the chamber. | і тіні камери. |

| At length there broke in upon my dreams a cry as of | Згодом у мої мрії увірвався крик |

| horror and dismay; | жах і жах; |

| and thereunto, after a pause, succeeded the sound of troubled | і до цього, після паузи, пролунав звук занепокоєння |

| voices, intermingled with many low moanings of sorrow, or of pain. | голоси, змішані з багатьма тихими стогонами смутку або болю. |

| I arose from my | Я виник із свого |

| seat and, throwing open one of the doors of the library, saw standing out in the | сидіння і, відчинивши одні з дверей бібліотеки, побачив, що стоїть у |

| antechamber a servant maiden, all in tears, who told me that Berenice was —no | передпокої служниця, вся в сльозах, яка сказала мені, що Береніс — ні |

| more. | більше. |

| She had been seized with epilepsy in the early morning, and now, | Рано вранці її охопила епілепсія, а тепер, |

| at the closing in of | на закриття з |

| the night, the grave was ready for its tenant, and all the preparations for the | ночі, могила була готова до свого орендаря, і всі приготування до |

| burial | поховання |

| were completed. | були завершені. |

| I found myself sitting in the library, and again sitting there | Я помітив, що сиджу в бібліотеці, і знову сиджу там |

| alone. | поодинці. |

| It | Це |

| seemed that I had newly awakened from a confused and exciting dream. | здавалося, що я щойно прокинувся від заплутаного та хвилюючого сну. |

| I knew that it | Я знав, що це |

| was now midnight, and I was well aware that since the setting of the sun | була опівніч, і я добре це усвідомлював із заходом сонця |

| Berenice had | Береніс мала |

| been interred. | був похований. |

| But of that dreary period which intervened I had no positive —at | Але про той сумний період, який втрутився, я не мав позитиву — в |

| least | найменше |

| no definite comprehension. | без певного розуміння. |

| Yet its memory was replete with horror —horror more | Проте його пам’ять була сповнена жаху — жаху більше |

| horrible from being vague, and terror more terrible from ambiguity. | жахливий від невизначеності, а жахливіший від двозначності. |

| It was a fearful | Це було страшно |

| page in the record my existence, written all over with dim, and hideous, and | сторінка в записі про моє існування, написана скрізь тьмяним, огидним і |

| unintelligible recollections. | незрозумілі спогади. |

| I strived to decypher them, but in vain; | Я намагався їх розшифрувати, але марно; |

| while ever and | колись і |

| anon, like the spirit of a departed sound, the shrill and piercing shriek of a | незабаром, як дух відійшов звук, пронизливий і пронизливий крик |

| female voice | жіночий голос |

| seemed to be ringing in my ears. | здавалося, дзвеніло в моїх вухах. |

| I had done a deed —what was it? | Я зробив вчинок — що це було? |

| I asked myself the | Я запитав себе |

| question aloud, and the whispering echoes of the chamber answered me, «what was | запитав вголос, і шепітне відлуння камери відповіло мені: «що було |

| it?» | це?» |

| On the table beside me burned a lamp, and near it lay a little box. | Біля мене на столі горіла лампа, а біля неї лежала коробочка. |

| It was of no | Це було ні |

| remarkable character, and I had seen it frequently before, for it was the | чудовий персонаж, і я бачив це часто раніше, бо це було |

| property of the | власність |

| family physician; | сімейний лікар; |

| but how came it there, upon my table, and why did I shudder in | але як воно опинилося там, на моєму столі, і чому я здригнувся |

| regarding it? | щодо цього? |

| These things were in no manner to be accounted for, and my eyes at | Ці речі жодним чином не можна було врахувати, і мої очі |

| length dropped to the open pages of a book, and to a sentence underscored | довжина опущена до відкритих сторінок книги та до підкресленого речення |

| therein. | там. |

| The | The |

| words were the singular but simple ones of the poet Ebn Zaiat, «Dicebant mihi sodales | слова були окремими, але простими словами поета Ебн Заіата, «Dicebant mihi sodales |

| si sepulchrum amicae visitarem, curas meas aliquantulum fore levatas. | si sepulchrum amicae visitarem, curas meas aliquantulum fore levatas. |

| «Why then, as I | «Чому тоді, як я |

| perused them, did the hairs of my head erect themselves on end, and the blood | дивився на них, чи волосся на моїй голові стало дибки, і кров |

| of my | мого |

| body become congealed within my veins? | тіло застигло в моїх венах? |

| There came a light tap at the library | У бібліотеці пролунав легкий постук |

| door, | двері, |

| and pale as the tenant of a tomb, a menial entered upon tiptoe. | і блідий, як орендар гробниці, слуга, що входить навшпиньки. |

| His looks were | Його вигляд був |

| wild | дикий |

| with terror, and he spoke to me in a voice tremulous, husky, and very low. | з жахом, і він заговорив до мене голосом тремтячим, хриплим і дуже низьким. |

| What said | Що сказав |

| he? | він? |

| —some broken sentences I heard. | — кілька уривчастих речень, які я чув. |

| He told of a wild cry disturbing the | Він розповів про дикий крик, який тривожив |

| silence of the | мовчання |

| night —of the gathering together of the household-of a search in the direction | ніч —зібрання домочадців-пошуку в напрямку |

| of the | з |

| sound; | звук; |

| —and then his tones grew thrillingly distinct as he whispered me of a | — а потім його тон став захоплююче виразним, коли він прошепотів мені про |

| violated | порушено |

| grave —of a disfigured body enshrouded, yet still breathing, still palpitating, | могила — спотворене тіло, яке все ще дихає, все ще серцебиться, |

| still alive! | досі живий! |

| He pointed to garments;-they were muddy and clotted with gore. | Він вказав на одяг; він був брудним і заляпався кров’ю. |

| I spoke not, | Я не говорив, |

| and he | і він |

| took me gently by the hand; | взяв мене ніжно за руку; |

| —it was indented with the impress of human nails. | — він був порізаний відбитком людських нігтів. |

| He | Він |

| directed my attention to some object against the wall; | звернув увагу на якийсь предмет біля стіни; |

| —I looked at it for some | — Я дивився на це для деяких |

| minutes; | хвилини; |

| —it was a spade. | — це була лопата. |

| With a shriek I bounded to the table, and grasped the box that | З криком я підскочив до столу і схопив коробку |

| lay | лежати |

| upon it. | на ньому. |

| But I could not force it open; | Але я не зміг відкрити його; |

| and in my tremor it slipped from my | і в моєму треморі воно вислизнуло з мене |

| hands, and | руки, і |

| fell heavily, and burst into pieces; | важко впав і розлетівся на шматки; |

| and from it, with a rattling sound, | і з нього, з деренчанням, |

| there rolled out | там викотили |

| some instruments of dental surgery, intermingled with thirty-two small, | деякі інструменти стоматологічної хірургії, змішані з тридцятьма двома маленькими, |

| white and | білий і |

| ivory-looking substances that were scattered to and fro about the floor. | речовини, схожі на слонову кістку, які були розкидані туди-сюди по підлозі. |

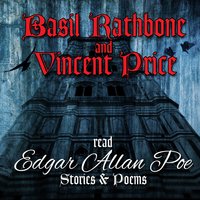

Переклад тексту пісні Berenice - Vincent Price, Basil Rathbone

Інформація про пісню На цій сторінці ви можете ознайомитися з текстом пісні Berenice , виконавця -Vincent Price

У жанрі:Саундтреки

Дата випуску:14.08.2013

Виберіть якою мовою перекладати:

Напишіть, що ви думаєте про текст пісні!

Інші пісні виконавця:

| Назва | Рік |

|---|---|

| 2013 | |

| 2013 | |

| 2013 | |

| 2013 |